For the Love Letters panel on October 18, 2020 at the Escape! festival Rod Oram shared the following letter and has very kindly agreed to allow us to be the first publisher of his piece of original writing.

____________________________________________________________________________

G’day Dag,

Writing a love letter to you feels a bit odd, to be honest.

First of all, down here in Aotearoa, calling someone a dag ... well, that’s not quite you.

And second, I’ve wanted to write to you for a very long time. But it was awkward. We’ve

never met. You’ve been dead since I was 10 years old. You did – and still do – hang out with

seriously cool people. Heck, say, kia ora from me next time you yarn with Jesus.

But now I have to write because the world’s such a mess.

To you Swedes, Dag means day. So often you bring daylight into my life, particularly in my

darkest days.

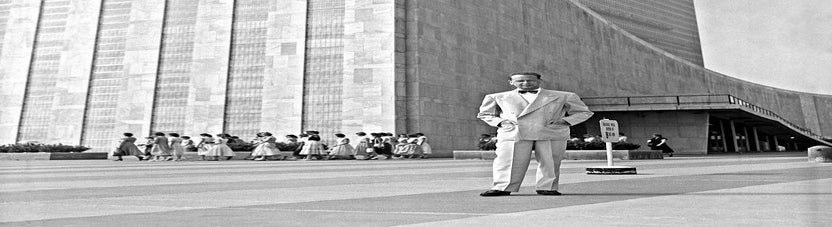

I know exactly when I first met you. It was after school on Tuesday, September 19th, 1961. I

was playing with my friend Chris Holmgren in the kitchen of his house, just three doors up

the road from mine in Birmingham, England.

His mother Daphne came in, tears streaming down her face.

“Dag’s dead,” she sobbed. “... in a plane crash.” I was shocked. I had no idea who you were.

But I’d never seen an adult so devastated. She tried to explain ... something about you trying

to being peace in a civil war. Was that a Swedish thing, I wondered? ... her husband, Chris’s

dad, Carl, was a Swedish American. Perhaps they knew you?

When I went home for tea, turned out my parents knew you too. They too had heard the

news. They told me you were head of the United Nations; the previous evening your plane

had crashed in northern Rhodesia when you were close to negotiating a cease fire in the

Congolese civil war; you were a great loss; with you dead, the world was more dangerous.

Only decades later did evidence emerge linking your plane crash to the CIA and a Belgian

multinational mining company operating in the Congo. You were 56.

Only then did I learn that the very same afternoon I was in the Holmgren’s kitchen, former

President Harry Truman said in Kansas that you were “on the point of getting something

done when they killed him. Notice that I said 'when they killed him'."

I didn’t meet you again until Christmas Day, 1969 … as it happened in Kansas. I was in the US

as an exchange student for an extra year of high school. I was staying in Topeka with the

family of a young music teacher from my school, David Woods, who remains a great friend

to this day.

David gave me a copy of your spiritual diary. Your first entry was when you were 20; the last

was a month before you were killed. Your title was Vägmärken, or Waymarks. Markings was

the translation WH Auden gave to his English edition. It was the only book you ever wrote. A

friend found the dairy in your papers after you died. Attached to it was your handwritten

note: “These entries provide the only true 'profile' that can be drawn ... If you find them

worth publishing, you have my permission to do so.”

My year at Colorado Academy changed my life. I’d arrived a frustrated, lost English

teenager. Teachers, friends and their families picked me up. I left with a sense of the

world’s wonder, of its infinite possibilities, good and bad. And you pointed me in the right

direction. In my commencement address, I quoted you, from page 205 of Markings:

“I don’t know Who – or what – put the question. I don’t know when it was put. I don’t even

remembering answering. But at that moment I did answer Yes to someone – or Something –

and from that hour I was certain that existence is meaningful and that, therefore, my life, in

self-surrender, had a goal.”

What was it about you? Why have I kept returning to you in Markings so often as I’ve

searched for waymarks on my journey down through the decades?

Well, I find that hard to express. But among many things it’s the opposite but

complimentary elements of your character which you held in remarkable balance: patience

and action; empathy and reserve; policy and people … to name a few.

But you always say things far better than I can so, you should have the last word in my

letter. For these troubled and treacherous times, I particularly like this from your Christmas

1953 speech at the United Nations, eight months after you were chosen as Secretary-General:

“Our work for peace must begin within the private world of each of us. To build for man a

world without fear, we must be without fear. To build a world of justice, we must be just.

And how can we fight for liberty if we are not free in our own minds? How can we ask

others to sacrifice if we are not ready to do so?

“Some might consider this to be just another expression of noble principles, too far from the

harsh realities of political life … I disagree.”

Aroha,

Rod